How "Christianity" Changed the World

Civilization itself was transformed as one religion spread across the globe, impacting every culture it touched.

In 31ad Jesus Christ founded His Church, which was to take His teachings and His message of the coming Kingdom of God to the world (Matthew 28:19-20). Those who were a part of this movement began to be called “Christians” (Acts 11:26). However, it was not long before an element of that faith began to diverge from the teachings of Jesus in significant ways (Jude 3). The religion that grew from this divergence—blending some of the biblical teachings and practices of Jesus with unbiblical teachings and practices from outside of the Bible—eventually gained the power and authority of Rome and the public label of “Christianity.”

The blending of biblical concepts and pagan ideas that this global, professing Christianity represents, as well as the remarkable ways in which God preserved the pure faith and teachings of true Christianity among a small flock, will be the subject of future articles in this series. But the historical record is clear: the hybrid religion that took Christ’s name had a powerful impact on civilization that is felt to this day around the world.

Transforming the Roman Empire

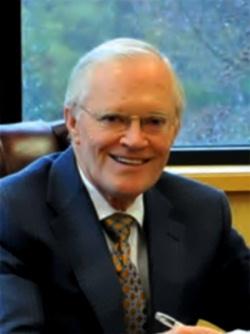

And such impact began soon in the Roman Empire, itself. Former professor of sociology Dr. Alvin Schmidt notes Elwood Cubberly’s observation that the biblical teachings of Jesus Christ challenged “almost everything for which the Roman world had stood” (How Christianity Changed the World, Schmidt, p. 44). Dr. James Kennedy writes, “Life was expendable prior to Christianity’s influence… In those days abortion was rampant. Abandonment was commonplace: It was common for infirm babies or unwanted little ones to be taken out into the forest or the mountainside, to be consumed by wild animals or to starve… They often abandoned female babies because women were considered inferior” (What If Jesus Had Never Been Born?, pp. 9–11).

The Romans promoted brutal gladiatorial contests where thousands of slaves, condemned criminals and prisoners of war mauled and slaughtered each other for the amusement of cheering audiences. Roman authors indicate that “sexual activity between men and women had become highly promiscuous and essentially depraved before and during the time that Christians appeared in Roman society” and that homosexuality was widespread among pagan Greeks and Romans, especially men with boys (Schmidt, pp. 79–86). Women were relegated to a low status in society, where they received little schooling, could not speak in public and were viewed as the property of their husbands (Schmidt, pp. 97–102).

As professing Christianity spread in the region, those parts of its teachings that corresponded to biblical truths had a profound impact. Pagan practices were confronted with biblical principles concerning the status of women and the importance of the family (Ephesians 5:22–33; 6:1–4), the sanctity of human life as made in God’s image (Genesis 1:26), and the sinfulness of sexual immorality and homosexuality (1 Corinthians 6:9–10). Eventually, Roman emperors even outlawed the branding of criminals and crucifixion and terminated the brutal gladiatorial contests that had flourished for nearly seven centuries—implementing one of the most important reforms in the moral history of mankind (Schmidt, p. 63–65). In the words of historian Christopher Dawson, the changes brought about by the spread of these ideas marked “the beginning of a new era in world history” (Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, p. 25).

Such changes were not limited to the West. The influence of biblical principles abolished suttee in India—the practice of burning widows on the funeral pyre of their husband. It stopped the killing of wives and concubines when tribal chiefs died in Africa, discouraged cannibalism, and helped to end the global slave trade in the 1800s (Kennedy, pp. 16–17).

Change Not Always Voluntary

Yet while it bore some biblical teachings in its doctrines and catechisms, this “Christianity” was a syncretic religion that combined some of the biblical teachings of Jesus with the beliefs, practices, and attitudes of many of the peoples it sought to “transform.”

Many of the same scholars who recognize the benefits that professing Christianity brought to the world as its influence increased also recognize that this increasing influence was often accomplished by very unbiblical and unchristian means. The history of movements such as the Spanish Inquisition, forcibly converting Jews and Muslims in Europe and elsewhere under pain of torture cannot be denied. Jesus taught His followers, “My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, My servants would fight” (John 18:36). But the religion that spread in His name thought otherwise, launching the Crusades and other militaristic efforts to create spaces where its influence could increase.

Burnings at the stake, beheadings, hangings and other executions of heretics and those unwilling to convert were characteristic of both the Roman Catholic and Protestant strains of professing Christianity (Schmidt, p. 293). The religion that was changing the world may have been called “Christianity,” but it was not truly the religion founded by Jesus Christ.

Impact on Modern World

Still, the impact of that religion continues to be visible in Western civilization today. Historians of professing Christianity have noted that “by the Middle Ages, Christianity had shaped Western culture, and it would continue to influence culture wherever [its teachings] spread” (Seven Revolutions, Aquilina & Papandrea, pp. 6–7). The charity encouraged by biblical teachings (e.g., Luke 10:30-37) eventually blossomed into hospitals, orphanages, homes for the elderly and care for the poor, the hungry and the homeless (Schmidt, pp. 147–148). Even many of the greatest and most prominent universities of our day were originally founded for “Christian” purposes (Kennedy, p. 40).

And while critics claim the Christian religion impeded the growth of science, history says otherwise. Dr. Rodney Stark, a professor of sociology and comparative religion, states, “the leading scientific figures in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries overwhelmingly were devout Christians who believed it was their duty to comprehend God’s handiwork” (For the Glory of God, p. 123). Unlike the godless religions of Asia and the capricious gods of other faiths, the God of the Bible was a rational Being whose creation operated on laws that were discoverable and could be applied to solving problems for the benefit of mankind (Psalm 19:1; Proverbs 25:2)—an understanding “essential for the rise of science” (Stark, p. 123).

Modern, atheistic critics can scoff at the beliefs of the Bible and the superstitions of professing Christianity, but they do so while benefitting from living in a culture built on many of the beliefs they detest. While in many ways it seems on the wane for the moment, the Bible prophesies that this apostate, professing Christianity will once again rise in power, not merely to influence the world, but to conquer it (Revelation 6:1-2), on a path that will take it into conflict with the true Christianity it has sought to leave behind (Revelation 13:11-17).

And in a very real way, the turning point in history that the spread of professing Christianity represented may presage a greater turning point to come.