Lost in the Multiverse

Is the multiverse real, in any of its proposed forms? Or is it just one more idea in a host of popular “scientific” theories meant to justify not believing in God?

I imagine that, as you live your life here on planet Earth, there is, somewhere, another you, living his or her life on another Earth as it travels around another sun, in another solar system, in another universe. Now imagine that there are an infinite number of those “other yous.” Some have lives very similar to yours—with the same job, the same friends, the same routine—and others have lives dramatically, almost unimaginably, different. Some are richer, some are poorer. Some are wealthy and famous, others are suffering in a cold, dark prison cell. And every one of them is every bit as real as you are.

Welcome to the multiverse.

First, a quick definition. You may have heard of the “metaverse”—that’s something different. The metaverse promises the use of artificial intelligence and computer screens, likely projected on eyeglasses or goggles, to augment our view of the world around us and immerse us in a tantalizing mixture of both computer-generated and real-world sensory inputs. The “multiverse,” by contrast, is the idea that our universe is just one among countless other universes, where statistics become meaningless as there are enough universes to account for every possible probability.

Variations on the multiverse have been staples of fantasy and science fiction for ages. And they are enjoying quite a renaissance on our cinema screens and streaming services. Media powerhouse Disney’s Marvel Entertainment invoked the idea of a multiverse to help its December 2021 hit Spider-Man: No Way Home rake in nearly $2 billion from moviegoers worldwide who were eager to see their favorite Spider-Men from multiple cinematic universes—Tom Holland, Andrew Garfield, and Tobey Maguire—fight bad guys together. (If you didn’t see this movie, imagine all the different James Bond actors teaming up to fight their old villains.) And, in May 2022, Marvel will make the multiverse center stage in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.

From Science Fiction to... Science Fact?

Yet the current interest in multiverse ideas is being fueled not by movie studios promoting fiction, but rather by an increasing number of scientists—theoretical physicists, cosmologists, and others—proposing it as reality. Influential physicist David Deutsch of the University of Oxford, for instance, has stated that we can be as confident of the multiverse as we are of the past existence of dinosaurs. As science writer Philip Ball notes in his 2020 book Beyond Weird, Deutsch says of believing in a multiverse, “The only astonishing thing is that that’s still controversial.”

For Deutsch and many other scientists, the multiverse scenario presented to us by science fiction movies and fantasy books—that reality is composed of an infinite collection of universes with infinite versions of you living infinitely different lives—is how reality truly is. If we don’t accept that “fact,” we are considered either ignorant or lacking the courage to embrace uncomfortable truths.

How have so many scientists, normally associated with evidence-based reasoning and a passion for hard facts, turned to a belief in a very theoretical multiverse?

The answers reveal much about the direction our culture and society are heading. And they show us just how far some people will go to avoid even the smallest acknowledgment of the possibility of a God who has created and designed our universe. But first, let’s notice that for all of Professor Deutsch’s bravado, there is no single “multiverse theory.” There are, perhaps fittingly, multiple multiverse theories in competition with each other:

Eternal or Chaotic Inflation: The current version of the Big Bang theory—the hypothesis that our universe of time, space, matter, and energy began as an infinitely dense singularity and expanded rapidly to become the growing cosmos we see around us—assumes that there was a brief but crucial period of cosmic inflation. During this temporary period, space in the very young universe, while it was still microscopic in scale, expanded faster than the speed of light. Such a period of inflation is seen as a solution to the unexpected uniformity of the vast cosmos.

However, influential physicists such as Andrei Linde and Alan Guth have noted that current models of inflation seem to imply that not only would our universe develop, but a collection of countless additional universes, as well—an endless process producing an infinite number of universes.

String Theory: In the search for a “Theory of Everything” that would unite all theories about the laws of nature, string theory has become very popular. While different strains of string theory exist, at their heart lies the idea that what we think of as fundamental particles of matter are actually incomprehensibly small, vibrating strings.

While the theory is considered extremely promising by many, it has its detractors. Among the concerns are the current inability to test whether the theory is true, along with the disconcerting fact that the number of unspecified parameters in the theory mean that 10500 (that’s a 1 with 500 zeros after it) universes could be generated from its equations. However, some see this not as a bug, but as a feature enabling a multiverse to exist, in which all possibilities are realized.

The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: For decades, most physicists working on quantum mechanics favored the idea that quantum objects do not hold particular values until they are measured. But a new idea is emerging—the “Many Worlds” interpretation—which suggests that quantum objects hold all potential values when measured, and that the universe splits into as many universes as there are values. It’s as if, when you rolled a six-sided die, you would see one result while five other versions of you would each see another result in another universe.

In a 2014 New Scientist article “Multiverse Me: Should I Care About My Other Selves?” (yes, that is a real title), physicist Deutsch summarizes the implications of the Many-Worlds Interpretation by noting that “when you make a choice the other choices also happen.” He adds, “If there is a small chance of an adverse consequence, say someone being killed, it seems on the face of it that we have to take into account the fact that in reality someone will be killed, if only in another universe.”

Max Tegmark’s “Ultimate Ensemble”: In perhaps the largest and wildest take on the multiverse, cosmologist Max Tegmark of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggests that the manner in which the universe around us seems to follow mathematical laws should point to a radical realization that math is the ultimate reality.

In Tegmark’s hypothesis, mathematical structures do not describe reality—rather, the mathematical structures are the reality, and the universe we see around us is simply a realization of one set of mathematical structures. As he writes in his 1998 paper in the Annals of Physics, “The only postulate in this theory is that all structures that exist mathematically exist also physically” (volume 270, issue 1). The result would be an impossible-to-imagine collection of universes that encompasses all possible laws of physics in all possible dimensions—a collection Tegmark has called the “Ultimate Ensemble.”

Existential Chaos

Before we look at how fact-based science has come to a place where such fantasies-turned-theories have been so thoroughly embraced, we should consider that each “multiverse” theory brings similar troubling consequences. If physicist Deutsch is correct, there exists a different universe for every possible result of every decision you could ever make. So, if you are tempted to lie, there is a universe in which you tell the truth, and a universe in which you lie. In this theory, free will is an illusion—you don’t really make a choice at all, since there are versions of you in multiple universes “choosing” every possibility. There would be a universe in which you kindly help an old lady cross the street, and there would be one in which you ignore her. But there would also be one in which you actively push her into the traffic, and one in which you steal her groceries for yourself.

The list of different universes—and different versions of you doing wildly different things—is essentially infinite. After all, if, as physicists imagine, you are only an assemblage of quarks, electrons, and so forth, and every possible combination of those particles happens in one universe or another, then there are universes beyond imagination in which you are doing all of these things.

It truly is existential chaos. And you have every right to call it out for the nonsense that it seems to be, for—regardless of how their descriptions fortify themselves with the feel of “hard science,” shine with a gleam borrowed from physics, and present themselves with the trustworthy air of mathematical inevitability—multiverse ideas are, in many ways, not much more than fantasy, far from the world of real science.

How Did We Get Here?

That raises a question: How did ideas that are so utterly fantastical in their conclusion come to be seen by so many as the mainstream views of physics and cosmology?

Is it that we have seen additional universes? Have we detected them in some way that requires us to accept their existence? Not at all. Attempts have been made—for example, some thought a cold spot in radiation that reaches Earth from space (which many believe to be an aftereffect of the Big Bang) might indicate a collision between our universe and another. Further analysis, however, showed that other features that should accompany such a collision, such as polarization of the radiation, simply were not present.

Not only have we failed to detect additional universes; according to most multiverse theories, those universes should be virtually undetectable. This has led many scientists to dismiss multiverse theories as blatantly unscientific. As mathematician George Ellis noted in the esteemed science magazine Nature, “The multiverse argument is a well-founded philosophical proposal but, as it cannot be tested, it does not belong fully in the scientific fold” (“Cosmology: The untestable multiverse,” Nature, January 20, 2011). In Ellis’ estimation, “Scientists are beginning to confuse science with science fiction.”

In fact, some have noted that the multiverse is worse than unscientific—it is a science killer.

Consider—in a multiverse wherein every event has taken place in at least one universe, no matter how improbable, there would be a universe in which every coin flip that has occurred throughout human history has come up “heads.” Extremely improbable? Yes! But impossible? No. In fact, in a multiverse, there must be a universe in which that happens. How would the scientists of that universe explain this phenomenon? They wouldn’t be able to—because there would be no scientific explanation. They would simply have to throw up their hands in frustration, since no cause could be found that could ever explain this completely random effect.

That is a relatively small example, but it illustrates a problem many scientists have recognized: If the multiverse is true, and all possible events happen—if they happen infinitely in an infinite number of universes—then science becomes meaningless. Every happenstance can be explained as, “Well, I guess we’re just in one of those universes!”

This is not just a hypothetical scenario. The multiverse is being used in this very way in real scientific papers.

For example, evolutionary biologist Eugene V. Koonin has estimated that the odds of life beginning with an RNA molecule capable of performing replication and translation on the early earth—complex functions of life necessary for evolution to begin—are virtually nonexistent: 1 out of a number that would be written as a 1 with 1,017 zeros after it. Those are odds so ridiculously small as to be unimaginable.

This would normally be seen as the death knell for this evolution-friendly “origin of life” scenario. However, the multiverse comes to the rescue! Wielding the “magic” of an infinite multiverse, Koonin notes, “In an infinite universe (multiverse), emergence of highly complex systems by chance is inevitable.”

With the wave of a magical, multiversal wand, what was impossible now becomes “inevitable.” Such reasoning is a mockery of scientific thought. A theory that predicts everything actually predicts nothing at all. The multiverse is nothing less than the death of science.

Yet, in this last example, we finally come to the reason why the unscientific multiverse appeals to scientists. How did we find ourselves here, lost in the multiverse? Because too many in our society will accept whatever nonsense they must in order to live without acknowledging a Creator.

A Desperate Antidote to “God”

Science has long been “plagued” by an uncomfortable truth: Much of what we know points to the reality of a powerful God who created the world and cosmos around us. Just as evolutionists seek to explain away that evidence by ascribing it to time, chance, and the drive for survival, many cosmologists seek to explain away a Creator and Designer by appealing to the multiverse.

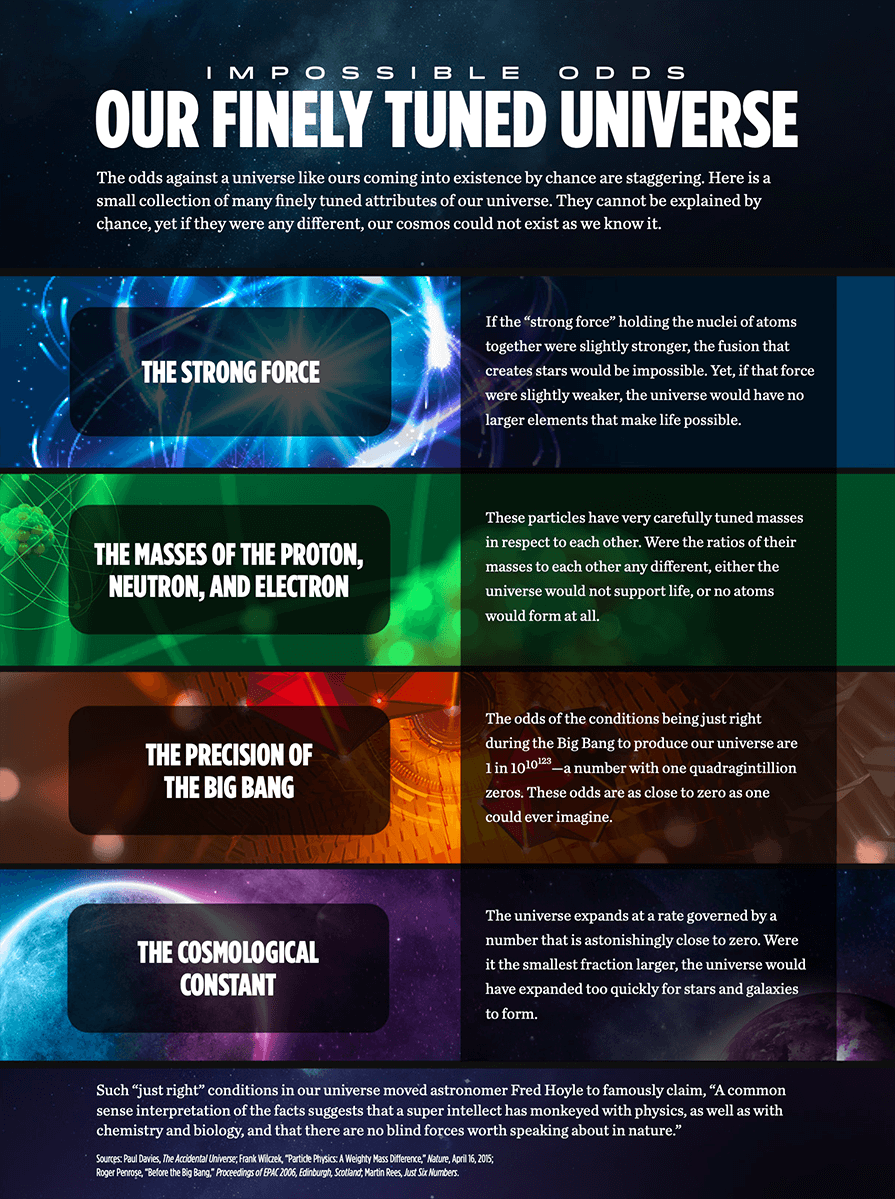

In a 2008 Discover magazine article appropriately titled “Science’s Alternative to an Intelligent Creator: The Multiverse Theory,” cosmologist Bernard Carr succinctly summarizes the issue: “If there is only one universe, you might have to have a fine-tuner. If you don’t want God, you’d better have a multiverse.”

You have to appreciate their honesty. Examples of this fine-tuning are endless, from the improbable masses of various fundamental particles to the precise strengths of the fundamental forces. And, while string theory suggests enough free variables and parameters to generate 10500 universes, the number of those that would produce a life-friendly universe is virtually nil. Without a fine-tuning God available to “tweak” the parameters to be “just right,” our existence should be considered impossible.

In just one attempt to estimate the probability of a universe like ours, the late physicist Lee Smolin estimated the probability to be 1 in 10229—that is, as a reminder, 1 out of a number that would be written normally as a 1 followed by 229 zeros. For those who like strange words, in English that would be “one in ten quinseptuagintillion.”

Yet even the multiverse and its vast, probabilistic resources are not enough to explain God away. Scientists such as Paul J. Steinhardt, who first introduced the hypothesis of “Eternal Inflation” to the world, has noted that inflation still requires unexplained fine-tuning to generate a multiverse. Physicist Alexander Vilenkin and colleagues have proven that an inflationary universe cannot be projected eternally into the past—so even a multiverse must have a beginning.

Perhaps it’s simplest to say that reports of the death of God at the hands of the multiverse have been greatly exaggerated.

A Philosophy Reflected in Society

There is a direct connection between the kind of thinking and reasoning that we see in multiverse theories and the deterioration into immorality and irrationality we see in society around us. The Apostle Paul warned us that denying the evidence of God imprinted on the universe would result in a world we would not want to live in. Decrying those who see the evidence of God’s existence but refuse to accept it, he noted the confusion, irrationality, and depravity that inevitably result from their purposeful ignorance.

And even as they did not like to retain God in their knowledge, God gave them over to a debased mind, to do those things which are not fitting; being filled with all unrighteousness, sexual immorality, wickedness, covetousness, maliciousness; full of envy, murder, strife, deceit, evil-mindedness; they are whisperers, backbiters, haters of God, violent, proud, boasters, inventors of evil things, disobedient to parents, undiscerning, untrustworthy, unloving, unforgiving, unmerciful; who, knowing the righteous judgment of God, that those who practice such things are deserving of death, not only do the same but also approve of those who practice them (Romans 1:28–32).

Only the willfully blind cannot see those conditions developing in our civilization today. Many are so desperate to avoid the conclusion that God exists, even when evidence of His providential hand is staring us in the face, that they will go to whatever lengths are necessary to reimagine existence without Him.

In cosmology, that sort of thinking leads to the irrational chaos of the multiverse. In society, it leads to the growing chaos and changing social mores we see around us every day. Rejecting a divine Designer lets us reimagine marriage as whatever we want it to be and deny that our gender is tied to our biology. It lets us justify murdering children in their mothers’ wombs. It lets monstrous ideologies call an entire race or nation “subhuman” to excuse genocide.

Sadly, it seems scientists and social engineers have a great deal in common; they will believe whatever fantasy they must believe in order to pretend that there is no God by whom they will one day be held accountable.

The Road Home: Embracing Reality

But we need not embrace the chaos. Gullible belief in the multiverse is not a requirement. Willful ignorance of reality is an obligation placed on no one.

In one sense, it doesn’t even matter whether God has created other universes; we are here, and we have the God-given ability to recognize the hand of the Creator in His creation (Romans 1:20). Scripture does not tell us that the truth of our world is accessible only to the minds of the finest scientists who can construct the most convoluted theories. Rather, it reminds us of the simplicity that is in Christ (2 Corinthians 11:3). God tells us that He has revealed His truth to “babes” (Matthew 11:25). We may marvel at the sheer creativity shown by those mathematicians, physicists, and philosophers who have gone to such elaborate lengths to explain reality while excluding God, but we should follow the actual principles of science and recognize that the simplest and most straightforward explanation is the correct one: There is a God who created our universe.

Science fiction and fantasy will continue to tell fantastic stories, some illustrated by intricate special effects, portraying imaginary worlds and fanciful versions of our own world. But we should not confuse such tale-telling for any semblance of reality, even when the line between scientists and storytellers is increasingly blurred.

Yes, the truth is simple and remarkable, and it is broadcast by all of creation: God exists. His hand is abundantly evident to those who are willing to see it. The fact that our universe—the universe we can see and touch, the only one we know is real—appears to be handcrafted for us to live in and learn about is no surprise to those who know their Creator lives. In fact, He makes Himself and His role in our existence plain in the pages of Scripture: “For thus says the Lord, who created the heavens, who is God, who formed the earth and made it, who has established it, who did not create it in vain, who formed it to be inhabited: ‘I am the Lord, and there is no other’” (Isaiah 45:18).